Clojure - Functional Programming for the JVM

By R. Mark Volkmann, OCI Partner

March 2009

Contents

| Introduction | Conditional Processing | Reference Types |

| Functional Programming | Iteration | Compiling |

| Clojure Overview | Recursion | Automated Testing |

| Getting Started | Predicates | Editors and IDEs |

| Clojure Syntax | Sequences | Desktop Applications |

| REPL | Input/Output | Web Applications |

| Vars | Destructuring | Databases |

| Collections | Namespaces | Libraries |

| StructMaps | Metadata | Conclusion |

| Defining Functions | Macros | References |

| Java Interoperability | Concurrency | |

Introduction

The goal of this article is to provide a fairly comprehensive introduction to the Clojure programming language. A large number of features are covered, each in a fairly brief manner. Feel free to skip around to the sections of most interest.

Please send feedback on errors and ways to improve explanations to mark@objectcomputing.com, or fork the repository and send a pull-request. I'm especially interested in feedback such as:

- You said X, but the correct thing to say is Y.

- You said X, but it would be more clear if you said Y.

- You didn't discuss X and I think it is an important topic.

Updates to this article that indicate the "last updated" date and provide a dated list of changes will be provided at https://objectcomputing.com/mark/clojure/. Also see my article on software transactional memory and the Clojure implementation of it at https://objectcomputing.com/mark/stm/.

Code examples in this article often show the return value of a function call or its output in a line comment (begins with a semicolon) followed by "->" and the result. For example:

(+ 1 2) ; showing return value -> 3

(println "Hello") ; return value is nil, showing output -> Hello

Functional Programming

Functional programming is a style of programming that emphasizes "first-class" functions that are "pure". It was inspired by ideas from the lambda calculus.

"Pure functions" are functions that always return the same result when passed the same arguments, as opposed to depending on state that can change with time. This makes them much easier to understand, debug and test. They have no side effects such as changing global state or performing any kind of I/O, including file I/O and database updates. State is maintained in the values of function parameters saved on the stack (often placed there by recursive calls) rather than in global variables saved on the heap. This allows functions to be executed repeatedly without affecting global state (an important characteristic to consider when transactions are discussed later). It also opens the door for smart compilers to improve performance by automatically reordering and parallelizing code, although the latter is not yet common.

In practice, applications need to have some side effects. Simon Peyton-Jones, a major contributor to the functional programming language Haskell, said the following: "In the end, any program must manipulate state. A program that has no side effects whatsoever is a kind of black box. All you can tell is that the box gets hotter." (http://oscon.blip.tv/file/324976) The key is to limit side effects, clearly identify them, and avoid scattering them throughout the code.

Languages that support "first-class functions" allow functions to be held in variables, passed to other functions and returned from them. The ability to return a function supports selection of behavior to be executed later. Functions that accept other functions as arguments are called "higher-order functions". In a sense, their operation is configured by the functions that are passed to them. The functions passed in can be executed any number of times, including not at all.

Data in functional programming languages is typically immutable. This allows data to be accessed concurrently from multiple threads without locking. There's no need to lock data that can't be changed. With multicore processors becoming prevalent, this simplification of programming for concurrency is perhaps the biggest benefit of functional programming.

If all of this sounds intriguing and you're ready to try functional programming, be prepared for a sizable learning curve. Many claim that functional programming isn't more difficult than object-oriented programming, it's just different. Taking the time to learn this style of programming is a worthwhile investment in order to obtain the benefits described above.

Popular functional programming languages include Clojure, Common Lisp, Erlang, F#, Haskell, ML, OCaml, Scheme and Scala. Clojure and Scala were written to run on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Other functional programming languages that have implementations that run on the JVM include: Armed Bear Common Lisp (ABCL), OCaml-Java and Kawa (Scheme).

Clojure Overview

Clojure is a dynamically-typed, functional programming language that runs on the JVM (Java 5 or greater) and provides interoperability with Java. A major goal of the language is to make it easier to implement applications that access data from multiple threads (concurrency).

Clojure is pronounced the same as the word "closure". The creator of the language, Rich Hickey, explains the name this way: "I wanted to involve C (C#), L (Lisp) and J (Java). Once I came up with Clojure, given the pun on closure, the available domains and vast emptiness of the googlespace, it was an easy decision."

Soon Clojure will also be available for the .NET platform. ClojureCLR is an implementation of Clojure that runs on the Microsoft Common Language Runtime instead of the JVM. At the time of this writing it is considered to be alpha quality.

In July 2011, ClojureScript was announced. It compiles Clojure code to JavaScript. See https://github.com/clojure/clojurescript.

Clojure is an open source language released under the Eclipse Public License v 1.0 (EPL). This is a very liberal license. See http://www.eclipse.org/legal/eplfaq.php for more information.

Running on the JVM provides portability, stability, performance and security. It also provides access to a wealth of existing Java libraries supporting functionality including file I/O, multithreading, database access, GUIs, web applications, and much more.

Each "operation" in Clojure is implemented as either a function, macro or special form. Nearly all functions and macros are implemented in Clojure source code. The differences between functions and macros are explained later. Special forms are recognized by the Clojure compiler and not implemented in Clojure source code. There are a relatively small number of special forms and new ones cannot be implemented. They include catch, def, do, dot ('.'), finally, fn, if, let, loop, monitor-enter, monitor-exit, new, quote, recur, set!, throw, try and var.

Clojure provides many functions that make it easy to operate on "sequences" which are logical views of collections. Many things can be treated as sequences. These include Java collections, Clojure-specific collections, strings, streams, directory structures and XML trees. New instances of Clojure collections can be created from existing ones in an efficient manner because they are persistent data structures.

Clojure provides three ways of safely sharing mutable data, all of which use mutable references to immutable data. Refs provide synchronous access to multiple pieces of shared data ("coordinated") by using Software Transactional Memory (STM). Atoms provide synchronous access to a single piece of shared data. Agents provide asynchronous access to a single piece of shared data. These are discussed in more detail in the "Reference Types" section.

Clojure is a Lisp dialect. However, it makes some departures from older Lisps. For example, older Lisps use the car function to get the first item in a list. Clojure calls this first as does Common Lisp. For a list of other differences, see http://clojure.org/lisps.

Lisp has a syntax that many people love ... and many people hate, mainly due to its use of parentheses and prefix notation. If you tend toward the latter camp, consider these facts. Many text editors and IDEs highlight matching parentheses, so it isn't necessary to count them in order to ensure they are balanced. Clojure function calls are less noisy than Java method calls. A Java method call looks like this:

methodName(arg1, arg2, arg3);A Clojure function call looks like this:

(function-name arg1 arg2 arg3)The open paren moves to the front and the commas and semicolon disappear. This syntax is referred to as a "form". There is simple beauty in the fact that everything in Lisp has this form. Note that the naming convention in Clojure is to use all lowercase with hyphens separating words in multi-word names, unlike the Java convention of using camelcase.

Defining functions is similarly less noisy in Clojure. The Clojure println function adds a space between the output from each of its arguments. To avoid this, pass the same arguments to the str function and pass its result to println .

- // Java

- public void hello(String name) {

- System.out.println("Hello, " + name);

- }

-

- ; Clojure

- (defn hello [name]

- (println "Hello," name))

Clojure makes heavy use of lazy evaluation. This allows functions to be invoked only when their result is needed. "Lazy sequences" are collections of results that are not computed until needed. This supports the efficient creation of infinite collections.

Clojure code is processed in three phases: read-time, compile-time and run-time. At read-time the Reader reads source code and converts it to a data structure, mostly a list of lists of lists. At compile-time this data structure is converted to Java bytecode. At run-time the bytecode is executed. Functions are only invoked at run-time. Macros are special constructs whose invocation looks similar to that of functions, but are expanded into new Clojure code at compile-time.

Is Clojure code hard to understand? Imagine if every time you read Java source code and encountered syntax elements like if statements, for loops, and anonymous classes, you had to pause and puzzle over what they mean. There are certain things that must be obvious to a person who wants to be a productive Java developer. Likewise there are parts of Clojure syntax that must be obvious for one to efficiently read and understand code. Examples include being comfortable with the use of let, apply, map, filter, reduce and anonymous functions ... all of which are described later.

Getting Started

Clojure code for your own library and application projects will typically reside in its own directory (named after the project) and will be managed by the Leiningen project management tool. Leiningen (or "lein" for short) will take care of downloading Clojure for you and making it available to your projects. To start using Clojure, you don't need to install Clojure, nor deal with jar files or the java command — just install and use lein (instructions on the Leiningen homepage, linked to above).

Once you've installed lein, create a trivial project to start playing around with:

- cd ~/temp

- lein new my-proj

- cd my-proj

- lein repl # starts up the interactive REPL

To create a new application project, do "lein new app my-app"

For more about getting started, see http://dev.clojure.org/display/doc/Getting+Started.

Clojure Syntax

Lisp dialects have a very simple, some would say beautiful, syntax. Data and code have the same representation, lists of lists that can be represented in memory quite naturally as a tree. (a b c)is a call to a function named a with arguments b and c. To make this data instead of code, the list needs to be quoted. '(a b c) or (quote (a b c)) is a list of the values a, b and c. That's it except for some special cases. The number of special cases there are depends on the dialect.

The special cases are seen by some as syntactic sugar. The more of them there are, the shorter certain kinds of code become and the more readers of the code have to learn and remember. It's a tricky balance. Many of them have an equivalent function name that can be used instead. I'll leave it to you to decide if Clojure has too much or too little syntactic sugar.

The table below briefly describes each of the special cases encountered in Clojure code. These will be described in more detail later. Don't try to understand everything in the table now.

| Purpose | Sugar | Function |

|---|---|---|

| comment | ; textfor line comments |

(comment text) macrofor block comments |

character literal (uses Java char type) |

\char \tab\newline \space\uunicode-hex-value |

(char ascii-code)(char \uunicode) |

string (uses Java String objects) |

"text" |

(str char1 char2 ...)concatenates characters and many other kinds of values to create a string. |

| keyword; an interned string; keywords with the same name refer to the same object; often used for map keys | :name |

(keyword "name") |

| keyword resolved in the current namespace | ::name |

none |

| regular expression | #"pattern"quoting rules differ from function form |

(re-pattern pattern) |

| treated as whitespace; sometimes used in collections to aid readability | , (a comma) |

N/A |

| list - a linked list | '(items)doesn't evaluate items |

(list items)evaluates items |

| vector - similar to an array | [items] |

(vector items) |

| set | #{items}creates a hash set |

(hash-set items)(sorted-set items) |

| map | {key-value-pairs}creates a hash map |

(hash-map key-value-pairs)(sorted-map key-value-pairs) |

| add metadata to a symbol or collection | ^{key-value-pairs}objectprocessed at read-time |

(with-meta objectmetadata-map)processed at run-time |

| get metadata map from a symbol or collection | (meta object) |

|

| gather a variable number of arguments in a function parameter list |

& name |

N/A |

| conventional name given to function parameters that aren't used |

_ (an underscore) |

N/A |

| construct a Java object; note the period after the class name |

(class-name. args) |

(new class-name args) |

| call a Java method | (. class-or-instancemethod-name args) or (.method-name class-or-instance args) |

none |

| call several Java methods, threading the result from each into the next as its first argument; each method can have additional arguments specified inside the parens; note the double period |

(.. class-or-object(method1 args) (method2 args) ...) |

none |

| create an anonymous function | #(single-expression)use % (same as %1), %1,%2 and so on for arguments |

(fn [arg-names]expressions) |

| dereference a Ref, Atom or Agent | @ref |

(deref ref) |

get Var object instead ofthe value of a symbol (var-quote) |

#'name |

(var name) |

| syntax quote (used in macros) | ` |

none |

| unquote (used in macros) | ~value |

(unquote value) |

| unquote splicing (used in macros) | ~@value |

none |

| auto-gensym (used in macros to generate a unique symbol name) | prefix# |

(gensym prefix?) |

Lisp dialects use prefix notation rather than the typical infix notation used by most programming languages for binary operators such as + and *. For example, in Java one might write a + b + c, whereas in a Lisp dialect this becomes (+ a b c). One benefit of this notation is that any number of arguments can be specified without repeating the operator. Binary operators from other languages are Lisp functions that aren't restricted to two operands.

One reason Lisp code contains more parentheses than code in other languages is that it also uses them where languages like Java use curly braces. For example, the statements in a Java method are inside curly braces, whereas the expressions in a Lisp function are inside the function definition which is surrounded by parentheses.

Compare the following snippets of Java and Clojure code that each define a simple function and invoke it. The output from both is "edray" and "orangeay".

- // This is Java code.

- public class PigLatin {

-

- public static String pigLatin(String word) {

- char firstLetter = word.charAt(0);

- if ("aeiou".indexOf(firstLetter) != -1) return word + "ay";

- return word.substring(1) + firstLetter + "ay";

- }

-

- public static void main(String args[]) {

- System.out.println(pigLatin("red"));

- System.out.println(pigLatin("orange"));

- }

- }

- ; This is Clojure code.

- ; When a set is used as a function, it returns the argument if it is

- ; in the set and nil otherwise. When used in a boolean context,

- ; that indicates whether the argument is in the set.

- (def vowel? (set "aeiou"))

-

- (defn pig-latin [word] ; defines a function

- ; word is expected to be a string

- ; which can be treated like a sequence of characters.

- (let [first-letter (first word)] ; assigns a local binding

- (if (vowel? first-letter)

- (str word "ay") ; then part of if

- (str (subs word 1) first-letter "ay")))) ; else part of if

-

- (println (pig-latin "red"))

- (println (pig-latin "orange"))

Clojure supports all the common data types such as booleans (with literal values of true and false), integers, decimals, characters (see "character literal" in the table above) and strings. It also supports ratios which retain a numerator and denominator so numeric precision is not lost when they are used in calculations.

Symbols are used to name things. These names are scoped in a namespace, either one that is specified or the default namespace. Symbols evaluate to their value. To access the Symbol object itself, it must be quoted.

Keywords begin with a colon and are used as unique identifiers. Examples include keys in maps and enumerated values (such as :red, :green and :blue).

It is possible in Clojure, as it is in any programming language, to write code that is difficult to understand. Following a few guidelines can make a big difference. Write short, well-focused functions to make them easier to read, test and reuse. Use the "extract method" refactoring pattern often. Deeply nested function calls can be hard to read. Limit this nesting where possible, often by using let to break complicated expressions into several less complicated expressions. Passing anonymous functions to named functions is common. However, avoid passing anonymous functions to other anonymous functions because such code is difficult to read.

REPL

REPL stands for read-eval-print loop. This is a standard tool in Lisp dialects that allows a user to enter expressions, have them read and evaluated, and have their result printed. It is a very useful tool for testing and gaining an understanding of code.

To start a REPL, enter "lein repl" at a command prompt. This will display a prompt of "user=>". The part before "=>" indicates the current default namespace. Forms entered after this prompt are evaluated and their result is output. Here's a sample REPL session that shows both input and output.

- user=> (def n 2)

- #'user/n

- user=> (* n 3)

- 6

def is a special form that doesn't evaluate its first argument, but instead uses the literal value as a name. Its REPL output shows that a symbol named "n" in the namespace "user" was defined.

To view documentation for a function, macro or namespace, enter (doc name). If it is a macro, the word "Macro" will appear on a line by itself immediately after its parameter list. The item for which documentation is being requested must already be loaded (see the require function). For example:

- (require 'clojure.string)

- (doc clojure.string/join) ; ->

- ; -------------------------

- ; clojure.string/join

- ; ([coll] [separator coll])

- ; Returns a string of all elements in coll, as returned by (seq coll),

- ; separated by an optional separator.

To find documentation on all functions/macros whose name or documentation string contains a given string, enter (find-doc "text").

To see the source for a function/macro, enter (source name). source is a macro defined in the clojure.repl namespace which is automatically loaded in the REPL environment.

To load and execute the forms in a source file, enter (load-file "file-path"). Typically these files have a .clj extension.

To exit the REPL under Windows, type ctrl-z followed by the enter key or just ctrl-c. To exit the REPL on every other platform (including UNIX, Linux and Mac OS X), type ctrl-d.

Vars

Clojure provides bindings to Vars, which are containers bound to mutable storage locations. There are global bindings, thread-local bindings, bindings that are local to a function, and bindings that are local to a given form.

Function parameters are bound to Vars that are local to the function.

The def special form binds a value to a symbol. It provides a mechanism to define metadata, :dynamic, which allows a thread-local value within the scope of a binding call. In other words, it allows re-definition of assigned value per execution thread and scope. If the Var is not re-assigned to a new value in a separate execution thread, the Var refers to the value of the root binding, if accessed from another thread.

The let special form creates bindings to Vars that are bound to the scope within the statement. Its first argument is a vector containing name/expression pairs. The expressions are evaluated in order and their results are assigned to the names on their left. These Vars can be used in the binding of other Vars declared within the vector. The expressions following the Var declaration vector contain the Var(s) that are executed only within the let scope. Vars within functions that are called within let but defined outside of that scope are not affected by the declarations in thelet's vector.

The binding macro is similar to let, but it gives new, thread-local values to existing global bindings throughout the scope's thread of execution. The values of Vars bound within the let vector argument are also used in functions, if they use the same Var names, called from inside that scope. When the execution thread leaves the binding macro's scope, the global Var bindings revert to their previous values. Starting in Clojure 1.3, binding can only do this for vars declared :dynamic.

Vars intended to be bound to new, thread-local values using binding have their own naming convention. These symbols have names that begin and end with an asterisk. Examples that appear in this article include *command-line-args*, *agent*, *err*, *flush-on-newline*,*in*, *load-tests*, *ns*, *out*, *print-length*, *print-level* and *stack-trace-depth*. Functions that use these bindings are affected by their values. For example, binding a new value to *out* changes the output destination of the println function.

The following code demonstrates usage of def, defn, let, binding, and println.

- (def ^:dynamic v 1) ; v is a global binding

-

- (defn f1 []

- (println "f1: v:" v))

-

- (defn f2 []

- (println "f2: before let v:" v)

- ; creates local binding v that shadows global one

- (let [v 2]

- ; local binding only within this let statement

- (println "f2: in let, v:" v)

- (f1))

- ; outside of this let, v refers to global binding

- (println "f2: after let v:" v))

-

- (defn f3 []

- (println "f3: before binding v:" v)

- ; same global binding with new, temporary value

- (binding [v 3]

- ; global binding, new value

- (println "f3: within binding function v: " v)

- (f1)) ; calling f1 with new value to v

- ; outside of binding v refers to first global value

- (println "f3: after binding v:" v))

-

- (defn f4 []

- (def v 4)) ; changes the value of v in the global scope

-

- (println "(= v 1) => " (= v 1))

- (println "Calling f2: ")

- (f2)

- (println)

- (println "Calling f3: ")

- (f3)

- (println)

- (println "Calling f4: ")

- (f4)

- (println "after calling f4, v =" v)

To run the code above, save it in a file named "vars.clj" and use the shell script for executing Clojure files described earlier as follows:

$ clj vars.cljThe output produced by the code above follows:

; (= v 1) => true

Calling f2

f2: before let v: 1

f2: in let, v: 2

f1: v: 1

f2: after let v: 1

Calling f3

f3: before binding v: 1

f3: within binding function v: 3

f1: v: 3

f3: after binding v: 1

Calling f4

after calling f4, v: 4Recap:

Notice in the first call to f2, the let function's binding to v did not change its originally declared value, as is shown in the call to f1 within the let statement. The value of v in f1 is 1, not 2.

Next, inside f3 within the scope of the binding call, the value of v was re-assigned within f1 since f1 was called within the execution thread of binding call's scope. Once f3's function execution thread exits from the binding call, v is bound to the initially declared binding, 1.

When f4 is called, the binding of v is not within the context of a new execution thread so v is bound to the new value, 4, in the global scope. Remember that changing a global value is not necessarily a best practice. It is presented in f4's definition for demonstration purposes.

Collections

Clojure provides the collection types list, vector, set and map. Clojure can also use any of the Java collection classes, but this is not typically done because the Clojure variety are a much better fit for functional programming.

The Clojure collection types have characteristics that differ from Java's collection types. All of them are immutable, heterogeneous and persistent. Being immutable means that their contents cannot be changed. Being heterogeneous means that they can hold any kind of object. Being persistent means that old versions of them are preserved when new versions are created. Clojure does this in a very efficient manner where new versions share memory with old versions. For example, a new version of a map containing thousands of key/value pairs where just one value needs to be modified can be created quickly and consumes very little additional memory.

There are many core functions that operate on all kinds of collections ... far too many to describe here. A small subset of them are described next using vectors. Keep in mind that since Clojure collections are immutable, there are no functions that modify them. Instead, there are many functions that use the magic of persistent data structures to efficiently create new collections from existing ones. Also, some functions that operate on a collection (for example, a vector) return a collection of a different type (for example, a LazySeq) that has different characteristics.

WARNING: This section presents information about Clojure collections that is important to learn. However, it drones on a bit, presenting function after function for operating on various types of collections. Should drowsiness set in, please skip ahead to the sections that follow and return to this section later.

The count function returns the number of items in any collection. For example:

(count [19 "yellow" true]) ; -> 3The conj function, short for conjoin, adds one or more items to a collection. Where they are added depends on the type of the collection. This is explained in the information on specific collection types below.

The reverse function returns a sequence of the items in the collection in reverse order.

(reverse [2 4 7]) ; -> (7 4 2)The map function applies a given function that takes one parameter to each item in a collection, returning a lazy sequence of the results. It can also apply functions that take more than one parameter if a collection is supplied for each argument. If those collections contain different numbers of items, the items used from each will be those at the beginning up to the number of items in the smallest collection. For example:

; The next line uses an anonymous function that adds 3 to its argument.

(map #(+ % 3) [2 4 7]) ; -> (5 7 10)

(map + [2 4 7] [5 6] [1 2 3 4]) ; adds corresponding items -> (8 12)The apply function returns the result of a given function when all the items in a given collection are used as arguments. For example:

apply + [2 4 7]); -> 13There are many functions that retrieve a single item from a collection. For example:

(def stooges ["Moe" "Larry" "Curly" "Shemp"])

(first stooges) ; -> "Moe"

(second stooges) ; -> "Larry"

(last stooges) ; -> "Shemp"

(nth stooges 2) ; indexes start at 0 -> "Curly"There are many functions that retrieve several items from a collection. For example:

(next stooges) ; -> ("Larry" "Curly" "Shemp")

(butlast stooges) ; -> ("Moe" "Larry" "Curly")

(drop-last 2 stooges) ; -> ("Moe" "Larry")

; Get names containing more than three characters.

(filter #(> (count %) 3) stooges) ; -> ("Larry" "Curly" "Shemp")

(nthnext stooges 2) ; -> ("Curly" "Shemp")There are several predicate functions that test the items in a collection and have a boolean result. These "short-circuit" so they only evaluate as many items as necessary to determine their result. For example:

(every? #(instance? String %) stooges) ; -> true

(not-every? #(instance? String %) stooges) ; -> false

(some #(instance? Number %) stooges) ; -> nil

(not-any? #(instance? Number %) stooges) ; -> trueLists

Lists are ordered collections of items. They are ideal when new items will be added to or removed from the front (constant-time). They are not efficient (linear time) for finding items by index (using nth) and there is no efficient way to change items by index.

Here are some ways to create a list that all have the same result:

(def stooges (list "Moe" "Larry" "Curly"))

(def stooges (quote ("Moe" "Larry" "Curly")))

(def stooges '("Moe" "Larry" "Curly"))The some function can be used to determine if a collection contains a given item. It takes a predicate function and a collection. While it may seem tedious to need to specify a predicate function in order to test for the existence of a single item, it is somewhat intentional to discourage this usage. Searching a list for a single item is a linear operation. Using a set instead of a list is more efficient and easier. Nevertheless, it can be done as follows:

(some #(= % "Moe") stooges) ; -> true

(some #(= % "Mark") stooges) ; -> nil

; Another approach is to create a set from the list

; and then use the contains? function on the set as follows.

(contains? (set stooges) "Moe") ; -> trueBoth the conj and cons functions create a new list that contains additional items added to the front. The remove function creates a new list containing only the items for which a predicate function returns false. For example:

(def more-stooges (conj stooges "Shemp")) ; -> ("Shemp" "Moe" "Larry" "Curly")

(def less-stooges (remove #(= % "Curly") more-stooges)) ; -> ("Shemp" "Moe" "Larry")The into function creates a new list that contains all the items in two lists. For example:

(def kids-of-mike '("Greg" "Peter" "Bobby"))

(def kids-of-carol '("Marcia" "Jan" "Cindy"))

(def brady-bunch (into kids-of-mike kids-of-carol))

(println brady-bunch) ; -> (Cindy Jan Marcia Greg Peter Bobby)The peek and pop functions can be used to treat a list as a stack. They operate on the beginning or head of the list.

Vectors

Vectors are also ordered collections of items. They are ideal when new items will be added to or removed from the back (constant-time). This means that using conj is more efficient than cons for adding items. They are efficient (constant time) for finding (using nth) or changing (using assoc) items by index. Function definitions specify their parameter list using a vector.

Here are some ways to create a vector:

(def stooges (vector "Moe" "Larry" "Curly"))

(def stooges ["Moe" "Larry" "Curly"])Unless the list characteristic of being more efficient at adding to or removing from the front is significant for a given use, vectors are typically preferred over lists. This is mainly due to the vector syntax of [...] being a bit more appealing than the list syntax of '(...). It doesn't have the possibility of being confused with a call to a function, macro or special form.

The get function retrieves an item from a vector by index. As shown later, it also retrieves a value from a map by key. Indexes start from zero. The get function is similar to the nth function. Both take an optional value to be returned if the index is out of range. If this is not supplied and the index is out of range, get returns nil and nth throws an exception. For example:

(get stooges 1 "unknown") ; -> "Larry"

(get stooges 3 "unknown") ; -> "unknown"The assoc function operates on vectors and maps. When applied to a vector, it creates a new vector where the item specified by an index is replaced. If the index is equal to the number of items in the vector, a new item is added to the end. If it is greater than the number of items in the vector, an IndexOutOfBoundsException is thrown. For example:

(assoc stooges 2 "Shemp") ; -> ["Moe" "Larry" "Shemp"]The subvec function returns a new vector that is a subset of an existing one that retains the order of the items. It takes a vector, a start index and an optional end index. If the end index is omitted, the subset runs to the end. The new vector shares the structure of the original one.

All the code examples provided above for lists also work for vectors. The peek and pop functions also work with vectors, but operate on the end or tail rather than the beginning or head as they do for lists. The conj function creates a new vector that contains an additional item added to the back. The cons function creates a new vector that contains an additional item added to the front.

Sets

Sets are collections of unique items. They are preferred over lists and vectors when duplicates are not allowed and items do not need to be maintained in the order in which they were added. Clojure supports two kinds of sets, unsorted and sorted. If the items being added to a sorted set can't be compared to each other, a ClassCastException is thrown. Here are some ways to create a set:

(def stooges (hash-set "Moe" "Larry" "Curly")) ; not sorted

(def stooges #{"Moe" "Larry" "Curly"}) ; same as previous

(def stooges (sorted-set "Moe" "Larry" "Curly"))The contains? function operates on sets and maps. When used on a set, it determines whether the set contains a given item. This is much simpler than using the some function which is needed to test this with a list or vector. For example:

(contains? stooges "Moe") ; -> true

(contains? stooges "Mark") ; -> false Sets can be used as functions of their items. When used in this way, they return the item or nil. This provides an even more compact way to test whether a set contains a given item. For example:

(stooges "Moe") ; -> "Moe"

(stooges "Mark") ; -> nil

(println (if (stooges person) "stooge" "regular person"))The conj and into functions demonstrated above with lists also work with sets. The location where the items are added is only defined for sorted sets.

The disj function creates a new set where one or more items are removed. For example:

(def more-stooges (conj stooges "Shemp")) ; -> #{"Moe" "Larry" "Curly" "Shemp"}

(def less-stooges (disj more-stooges "Curly")) ; -> #{"Moe" "Larry" "Shemp"}Also consider the functions in the clojure.set namespace which include: difference, index,intersection, join, map-invert, project, rename, rename-keys, select and union. Some of these functions operate on maps instead of sets.

Maps

Maps store associations between keys and their corresponding values where both can be any kind of object. Often keywords are used for map keys. Entries can be stored in such a way that the pairs can be quickly retrieved in sorted order based on their keys.

Here are some ways to create maps that store associations from popsicle colors to their flavors where the keys and values are both keywords. The commas aid readability. They are optional and are treated as whitespace.

(def popsicle-map

(hash-map :red :cherry, :green :apple, :purple :grape))

(def popsicle-map

{:red :cherry, :green :apple, :purple :grape}) ; same as previous

(def popsicle-map

(sorted-map :red :cherry, :green :apple, :purple :grape))Maps can be used as functions of their keys. Also, in some cases keys can be used as functions of maps. For example, keyword keys can, but string and integer keys cannot. The following are all valid ways to get the flavor of green popsicles, which is :apple:

(get popsicle-map :green)

(popsicle-map :green)

(:green popsicle-map)The contains? function operates on sets and maps. When used on a map, it determines whether the map contains a given key. The keys function returns a sequence containing all the keys in a given map. The vals function returns a sequence containing all the values in a given map. For example:

(contains? popsicle-map :green) ; -> true

(keys popsicle-map) ; -> (:red :green :purple)

(vals popsicle-map) ; -> (:cherry :apple :grape)The assoc function operates on maps and vectors. When applied to a map, it creates a new map where any number of key/value pairs are added. Values for existing keys are replaced by new values. For example:

(assoc popsicle-map :green :lime :blue :blueberry)

; -> {:blue :blueberry, :green :lime, :purple :grape, :red :cherry}The dissoc function takes a map and any number of keys. It returns a new map where those keys are removed. Specified keys that aren't in the map are ignored. For example:

(dissoc popsicle-map :green :blue) ; -> {:purple :grape, :red :cherry}When used in the context of a sequence, maps are treated like a sequence of clojure.lang.MapEntry objects. This can be combined with the use of doseq and destructuring, both of which are described in more detail later, to easily iterate through all the keys and values. The following example iterates through all the key/value pairs in popsicle-map and binds the key to color and the value to flavor. The name function returns the string name of a keyword.

(doseq [[color flavor] popsicle-map]

(println (str "The flavor of " (name color)

" popsicles is " (name flavor) ".")))The output produced by the code above follows:

The flavor of green popsicles is apple.

The flavor of purple popsicles is grape.

The flavor of red popsicles is cherry.The select-keys function takes a map and a sequence of keys. It returns a new map where only those keys are in the map. Specified keys that aren't in the map are ignored. For example:

(select-keys popsicle-map [:red :green :blue]) ; -> {:green :apple, :red :cherry}The conj function adds all the key/value pairs from one map to another. If any keys in the source map already exist in the target map, the target map values are replaced by the corresponding source map values.

Values in maps can be maps, and they can be nested to any depth. Retrieving nested values is easy. Likewise, creating new maps where nested values are modified is easy.

To demonstrate this we'll create a map that describes a person. It has a key whose value describes their address using a map. It also has a key whose value describes their employer which has its own address map.

(def person {

:name "Mark Volkmann"

:address {

:street "644 Glen Summit"

:city "St. Charles"

:state "Missouri"

:zip 63304}

:employer {

:name "Object Computing, Inc."

:address {

:street "12140 Woodcrest Executive Drive, Suite 250"

:city "Creve Coeur"

:state "Missouri"

:zip 63141}}})The get-in function takes a map and a key sequence. It returns the value of the nested map key at the end of the sequence. The -> macro and the reduce function can also be used for this purpose. All of these are demonstrated below to retrieve the employer city which is "Creve Coeur".

(get-in person [:employer :address :city])

(-> person :employer :address :city) ; explained below

(reduce get person [:employer :address :city]) ; explained belowThe -> macro, referred to as the "thread" macro, calls a series of functions, passing the result of each as an argument to the next. For example the following lines have the same result:

(f1 (f2 (f3 x)))

(-> x f3 f2 f1)There is also a -?> macro in the clojure.core.incubator namespace that stops and returns nil if any function in the chain returns nil. This avoids getting a NullPointerException.

The reduce function takes a function of two arguments, an optional value and a collection. It begins by calling the function with either the value and the first item in the collection or the first two items in the collection if the value is omitted. It then calls the function repeatedly with the previous function result and the next item in the collection until every item in the collection has been processed. This function is the same as inject in Ruby and foldl in Haskell.

The assoc-in function takes a map, a key sequence and a new value. It returns a new map where the nested map key at the end of the sequence has the new value. For example, a new map where the employer city is changed to "Clayton" can be created as follows:

assoc-in person [:employer :address :city] "Clayton")The update-in function takes a map, a key sequence, a function and any number of additional arguments. The function is passed the old value of the key at the end of the sequence and the additional arguments. The value it returns is used as the new value of that key. For example, a new map where the employer zip code is changed to a string in the U.S. "ZIP + 4" format can be created using as follows:

(update-in person [:employer :address :zip] str "-1234") ; using the str function

StructMaps

Note: StructMaps have been deprecated. Records are generally recommended instead. A section on Records will be added shortly.

StructMaps are similar to regular maps, but are optimized to take advantage of common keys in multiple instances so they don't have to be repeated. Their use is similar to that of Java Beans. Proper equals and hashCode methods are generated for them. Accessor functions that are faster than ordinary map key lookups can easily be created.

The create-struct function and defstruct macro, which uses create-struct, both define StructMaps. The keys are normally specified with keywords. For example:

(def vehicle-struct (create-struct :make :model :year :color)) ; long way

(defstruct vehicle-struct :make :model :year :color) ; short wayThe struct function creates an instance of a given StructMap. Values must be specified in the same order as their corresponding keys were specified when the StructMap was defined. Values for keys at the end can be omitted and their values will be nil. For example:

(def vehicle (struct vehicle-struct "Toyota" "Prius" 2009))The accessor function creates a function for accessing the value of a given key in instances that avoids performing a hash map lookup. For example:

; Note the use of def instead of defn because accessor returns

; a function that is then bound to "make".

(def make (accessor vehicle-struct :make))

(make vehicle) ; -> "Toyota"

(vehicle :make) ; same but slower

(:make vehicle) ; same but slowerNew keys not specified when the StructMap was defined can be added to instances. However, keys specified when the StructMap was defined cannot be removed from instances.

Defining Functions

The defn macro defines a function. Its arguments are the function name, an optional documentation string (displayed by the doc macro), the parameter list (specified with a vector that can be empty) and the function body. The result of the last expression in the body is returned. Every function returns a value, but it may be nil. For example:

(defn parting

"returns a String parting"

[name]

(str "Goodbye, " name)) ; concatenation

(println (parting "Mark")) ; -> Goodbye, MarkFunction definitions must appear before their first use. Sometimes this isn't possible due to a set of functions that invoke each other. The declare special form takes any number of function names and creates forward declarations that resolve these cases. For example:

(declare function-names)Functions defined with the defn- macro are private. This means they are only visible in the namespace in which they are defined. Other macros that produce private definitions, such as defmacro-, are in clojure.core.incubator.

Functions can take a variable number of parameters. Optional parameters must appear at the end. They are gathered into a list by adding an ampersand and a name for the list at the end of the parameter list.

(defn power [base & exponents]

; Using java.lang.Math static method pow.

(reduce #(Math/pow %1 %2) base exponents))

(power 2 3 4) ; 2 to the 3rd = 8; 8 to the 4th = 4096Function definitions can contain more than one parameter list and corresponding body. Each parameter list must contain a different number of parameters. This supports overloading functions based on arity. Often it is useful for a body to call the same function with a different number of arguments in order to provide default values for some of them. For example:

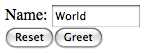

(defn parting

"returns a String parting in a given language"

([] (parting "World"))

([name] (parting name "en"))

([name language]

; condp is similar to a case statement in other languages.

; It is described in more detail later.

; It is used here to take different actions based on whether the

; parameter "language" is set to "en", "es" or something else.

(condp = language

"en" (str "Goodbye, " name)

"es" (str "Adios, " name)

(throw (IllegalArgumentException.

(str "unsupported language " language))))))

(println (parting)) ; -> Goodbye, World

(println (parting "Mark")) ; -> Goodbye, Mark

(println (parting "Mark" "es")) ; -> Adios, Mark

(println (parting "Mark", "xy"))

; -> java.lang.IllegalArgumentException: unsupported language xyAnonymous functions have no name. These are often passed as arguments to a named function. They are handy for short function definitions that are only used in one place. There are two ways to define them, shown below:

(def years [1940 1944 1961 1985 1987])

(filter (fn [year] (even? year)) years) ; long way w/ named arguments -> (1940 1944)

(filter #(even? %) years) ; short way where % refers to the argumentWhen an anonymous function is defined using the fn special form, the body can contain any number of expressions. It can also have a name (following "fn") which makes it no longer anonymous and enables it to call itself recursively.

When an anonymous function is defined in the short way using #(...), it can only contain a single expression. To use more than one expression, wrap them in the do special form. If there is only one parameter, it can be referred to with %. If there are multiple parameters, they are referred to with %1, %2 and so on. For example:

(defn pair-test [test-fn n1 n2]

(if (test-fn n1 n2) "pass" "fail"))

; Use a test-fn that determines whether

; the sum of its two arguments is an even number.

(println (pair-test #(even? (+ %1 %2)) 3 5)) ; -> passJava methods can be overloaded based on parameter types. Clojure functions can only be overloaded on arity. Clojure multimethods however, can be overloaded based on anything.

The defmulti and defmethod macros are used together to define a multimethod. The arguments to defmulti are the method name and the dispatch function which returns a value that will be used to select a method. The arguments to defmethod are the method name, the dispatch value that triggers use of the method, the parameter list and the body. The special dispatch value :default is used to designate a method to be used when none of the others match. Each defmethod for the same multimethod name must take the same number of arguments. The arguments passed to a multimethod are passed to the dispatch function.

Here's an example of a multimethod that overloads based on type.

(defmulti what-am-i class) ; class is the dispatch function

(defmethod what-am-i Number [arg] (println arg "is a Number"))

(defmethod what-am-i String [arg] (println arg "is a String"))

(defmethod what-am-i :default [arg] (println arg "is something else"))

(what-am-i 19) ; -> 19 is a Number

(what-am-i "Hello") ; -> Hello is a String

(what-am-i true) ; -> true is something elseSince the dispatch function can be any function, including one you write, the possibilities are endless. For example, a custom dispatch function could examine its arguments and return a keyword to indicate a size such as :small, :medium or :large. One method for each size keyword can provide logic that is specific to a given size.

Underscores can be used as placeholders for function parameters that won't be used and therefore don't need a name. This is often useful in callback functions which are passed to another function so they can be invoked later. A particular callback function may not use all the arguments that are passed to it. For example:

(defn callback1 [n1 n2 n3] (+ n1 n2 n3)) ; uses all three arguments

(defn callback2 [n1 _ n3] (+ n1 n3)) ; only uses 1st & 3rd arguments

(defn caller [callback value]

(callback (+ value 1) (+ value 2) (+ value 3)))

(caller callback1 10) ; 11 + 12 + 13 -> 36

(caller callback2 10) ; 11 + 13 -> 24

The complement function returns a new function that is just like a given function, but returns the opposite logical truth value. For example:

(defn teenager? [age] (and (>= age 13) (< age 20)))

(def non-teen? (complement teenager?))

(println (non-teen? 47)) ; -> trueThe comp function composes a new function by combining any number of existing ones. They are called from right to left. For example:

(defn times2 [n] (* n 2))

(defn minus3 [n] (- n 3))

; Note the use of def instead of defn because comp returns

; a function that is then bound to "my-composition".

(def my-composition (comp minus3 times2))

(my-composition 4) ; 4*2 - 3 -> 5The partial function creates a new function from an existing one so that it provides fixed values for initial parameters and calls the original function. This is called a "partial application". For example, * is a function that takes any number of arguments and multiplies them together. Suppose we want a new version of that function that always multiplies by two.

; Note the use of def instead of defn because partial returns

; a function that is then bound to "times2".

(def times2 (partial * 2))

(times2 3 4) ; 2 * 3 * 4 -> 24Here's an interesting use of both the map and partial functions. We'll define functions that use the map function to compute the value of an arbitrary polynomial and its derivative for given x values. The polynomials are described by a vector of their coefficients. Next, we'll define functions that use partial to define functions for a specific polynomial and its derivative. Finally, we'll demonstrate using the functions.

The range function returns a lazy sequence of integers from an inclusive lower bound to an exclusive upper bound. The lower bound defaults to 0, the step size defaults to 1, and the upper bound defaults to infinity.

(defn- polynomial

"computes the value of a polynomial

with the given coefficients for a given value x"

[coefs x]

; For example, if coefs contains 3 values then exponents is (2 1 0).

(let [exponents (reverse (range (count coefs)))]

; Multiply each coefficient by x raised to the corresponding exponent

; and sum those results.

; coefs go into %1 and exponents go into %2.

(apply + (map #(* %1 (Math/pow x %2)) coefs exponents))))

(defn- derivative

"computes the value of the derivative of a polynomial

with the given coefficients for a given value x"

[coefs x]

; The coefficients of the derivative function are obtained by

; multiplying all but the last coefficient by its corresponding exponent.

; The extra exponent will be ignored.

(let [exponents (reverse (range (count coefs)))

derivative-coefs (map #(* %1 %2) (butlast coefs) exponents)]

(polynomial derivative-coefs x)))

(def f (partial polynomial [2 1 3])) ; 2x^2 + x + 3

(def f-prime (partial derivative [2 1 3])) ; 4x + 1

(println "f(2) =" (f 2)) ; -> 13.0

(println "f'(2) =" (f-prime 2)) ; -> 9.0Here's an another way that the polynomial function could be implemented (suggested by Francesco Strino). For a polynomial with coefficients a, b and c, it computes the value for x as follows:

%1 = a, %2 = b, result is ax + b

%1 = ax + b, %2 = c, result is (ax + b)x + c = ax^2 + bx + c(defn- polynomial

"computes the value of a polynomial

with the given coefficients for a given value x"

[coefs x]

(reduce #(+ (* x %1) %2) coefs))The memoize function takes another function and returns a new function that stores a mapping from previous arguments to previous results for the given function. The new function uses the mapping to avoid invoking the given function with arguments that have already been evaluated. This results in better performance, but also requires memory to store the mappings.

The time macro evaluates an expression, prints the elapsed time, and returns the expression result. It is used in the following code to measure the time to compute the value of a polynomial at a given x value.

The following example demonstrates memoizing a polynomial function:

; Note the use of def instead of defn because memoize returns

; a function that is then bound to "memo-f".

(def memo-f (memoize f))

(println "priming call")

(time (f 2))

(println "without memoization")

; Note the use of an underscore for the binding that isn't used.

(dotimes [_ 3] (time (f 2)))

(println "with memoization")

(dotimes [_ 3] (time (memo-f 2)))The output produced by this code from a sample run is shown below.

priming call

"Elapsed time: 4.128 msecs"

without memoization

"Elapsed time: 0.172 msecs"

"Elapsed time: 0.365 msecs"

"Elapsed time: 0.19 msecs"

with memoization

"Elapsed time: 0.241 msecs"

"Elapsed time: 0.033 msecs"

"Elapsed time: 0.019 msecs"There are several observations than can be made from this output. The first call to the function f, the "priming call", takes considerably longer than the other calls. This is true regardless of whether memoization is used. The first call to the memoized function takes longer than the first non-priming call to the original function, due to the overhead of caching its result. Subsequent calls to the memoized function are much faster.

Java Interoperability

Clojure programs can use all Java classes and interfaces. As in Java, classes in the java.lang package can be used without importing them. Java classes in other packages can be used by either specifying their package when referencing them or using the import function. For example:

(import

'(java.util Calendar GregorianCalendar)

'(javax.swing JFrame JLabel))Also see the :import directive of the ns macro which is described later.

There are two ways to access constants in a Java class, shown in the examples below:

(. java.util.Calendar APRIL) ; -> 3

(. Calendar APRIL) ; works if the Calendar class was imported

java.util.Calendar/APRIL

Calendar/APRIL ; works if the Calendar class was importedInvoking Java methods from Clojure code is very easy. Because of this, Clojure doesn't provide functions for many common operations and instead relies on Java methods. For example, Clojure doesn't provide a function to find the absolute value of a floating point number because the abs method of the Java class java.lang.Math class already does that. On the other hand, while that class provides the method max to find the largest of two values, it only works with two values, so Clojure provides the max function which takes one or more values.

There are two ways to invoke a static method in a Java class, shown in the examples below:

(. Math pow 2 4) ; -> 16.0

(Math/pow 2 4)There are two ways to invoke a constructor to create a Java object, shown in the examples below. Note the use of the def special form to retain a reference to the new object in a global binding. This is not required. A reference could be retained in several other ways such as adding it to a collection or passing it to a function.

(import '(java.util Calendar GregorianCalendar))

(def calendar (new GregorianCalendar 2008 Calendar/APRIL 16)) ; April 16, 2008

(def calendar (GregorianCalendar. 2008 Calendar/APRIL 16))There are two ways to invoke an instance method on a Java object, shown in the examples below:

(. calendar add Calendar/MONTH 2)

(. calendar get Calendar/MONTH) ; -> 5

(.add calendar Calendar/MONTH 2)

(.get calendar Calendar/MONTH) ; -> 7The option in the examples above where the method name appears first is generally preferred. The option where the object appears first is easier to use inside macro definitions because syntax quoting can be used instead of string concatenation. This statement will make more sense after reading the "Macros" section ahead.

Method calls can be chained using the .. macro. The result from the previous method call in the chain becomes the target of the next method call. For example:

(. (. calendar getTimeZone) getDisplayName) ; long way

(.. calendar getTimeZone getDisplayName) ; -> "Central Standard Time"There is also a .?. macro in the clojure.core.incubator namespace that stops and returns nil if any method in the chain returns null. This avoids getting a NullPointerException.

The doto macro is used to invoke many methods on the same object. It returns the value of its first argument which is the target object. This makes it convenient to create the target object with an expression that is the first argument (see the creation of a JFrame GUI object in the "Namespaces" section ahead). For example:

(doto calendar

(.set Calendar/YEAR 1981)

(.set Calendar/MONTH Calendar/AUGUST)

(.set Calendar/DATE 1))

(def formatter (java.text.DateFormat/getDateInstance))

(.format formatter (.getTime calendar)) ; -> "Aug 1, 1981"The memfn macro expands to code that allows a Java method to be treated as a first class function. It is an alternative to using an anonymous function for calling a Java method. When using memfn to invoke Java methods that take arguments, a name for each argument must be specified. This indicates the arity of the method to be invoked. These names are arbitrary, but they must be unique because they are used in the generated code. The following examples apply an instance method (substring) to a Java object from the first collection (a String), passing the corresponding item from the second collection (an int) as an argument:

(println (map #(.substring %1 %2)

["Moe" "Larry" "Curly"] [1 2 3])) ; -> (oe rry ly)

(println (map (memfn substring beginIndex)

["Moe" "Larry" "Curly"] [1 2 3])) ; -> sameProxies

The proxy macro expands to code that creates a Java object that extends a given Java class and/or implements zero or more Java interfaces. This is often needed to implement callback methods in listener objects that must implement a certain interface in order to register for notifications from another object. For an example, see the "Desktop Applications" section near the end of this article. It creates an object that extends the JFrame GUI class and implements the ActionListener interface.

Threads

All Clojure functions implement both the java.lang.Runnable interface and the java.util.concurrent.Callable interface. This makes it easy to execute them in new Java threads. For example:

(defn delayed-print [ms text]

(Thread/sleep ms)

(println text))

; Pass an anonymous function that invokes delayed-print

; to the Thread constructor so the delayed-print function

; executes inside the Thread instead of

; while the Thread object is being created.

(.start (Thread. #(delayed-print 1000 ", World!"))) ; prints 2nd

(print "Hello") ; prints 1st

; output is "Hello, World!"Exception Handling

All exceptions thrown by Clojure code are runtime exceptions. Java methods invoked from Clojure code can still throw checked exceptions. The try, catch, finally and throw special forms provide functionality similar to their Java counterparts. For example:

(defn collection? [obj]

(println "obj is a" (class obj))

; Clojure collections implement clojure.lang.IPersistentCollection.

(or (coll? obj) ; Clojure collection?

(instance? java.util.Collection obj))) ; Java collection?

(defn average [coll]

(when-not (collection? coll)

(throw (IllegalArgumentException. "expected a collection")))

(when (empty? coll)

(throw (IllegalArgumentException. "collection is empty")))

; Apply the + function to all the items in coll,

; then divide by the number of items in it.

(let [sum (apply + coll)]

(/ sum (count coll))))

(try

(println "list average =" (average '(2 3))) ; result is a clojure.lang.Ratio object

(println "vector average =" (average [2 3])) ; same

(println "set average =" (average #{2 3})) ; same

(let [al (java.util.ArrayList.)]

(doto al (.add 2) (.add 3))

(println "ArrayList average =" (average al))) ; same

(println "string average =" (average "1 2 3 4")) ; illegal argument

(catch IllegalArgumentException e

(println e)

;(.printStackTrace e) ; if a stack trace is desired

)

(finally

(println "in finally")))The output produced by the code above follows:

obj is a clojure.lang.PersistentList

list average = 5/2

obj is a clojure.lang.LazilyPersistentVector

vector average = 5/2

obj is a clojure.lang.PersistentHashSet

set average = 5/2

obj is a java.util.ArrayList

ArrayList average = 5/2

obj is a java.lang.String

#<IllegalArgumentException java.lang.IllegalArgumentException:

expected a collection>

in finallyConditional Processing

The if special form tests a condition and executes one of two expressions based on whether the condition evaluates to true. Its syntax is (if condition then-expr else-expr). The else expression is optional. If more than one expression is needed for the then or else part, use the do special form to wrap them in a single expression. For example:

- (import '(java.util Calendar GregorianCalendar))

- (let [gc (GregorianCalendar.)

- day-of-week (.get gc Calendar/DAY_OF_WEEK)

- is-weekend (or (= day-of-week Calendar/SATURDAY) (= day-of-week Calendar/SUNDAY))]

- (if is-weekend

- (println "play")

- (do (println "work")

- (println "sleep"))))

The when and when-not macros provide alternatives to if when only one branch is needed. Any number of body expressions can be supplied without wrapping them in a do. For example:

(when is-weekend (println "play"))

(when-not is-weekend (println "work") (println "sleep"))The if-let macro binds a value to a single binding and chooses an expression to evaluate based on whether the value is logically true or false (explained in the "Predicates" section). The following code prints the name of the first person waiting in line or prints "no waiting" if the line is empty.

(defn process-next [waiting-line]

(if-let [name (first waiting-line)]

(println name "is next")

(println "no waiting")))

(process-next '("Jeremy" "Amanda" "Tami")) ; -> Jeremy is next

(process-next '()) ; -> no waitingThe when-let macro is similar to the if-let macro, but it differs in the same way that if differs from when. It doesn't support an else part and the then part can contain any number of expressions. For example:

(defn summarize

"prints the first item in a collection

followed by a period for each remaining item"

[coll]

; Execute the when-let body only if the collection isn't empty.

(when-let [head (first coll)]

(print head)

; Below, dec subtracts one (decrements) from

; the number of items in the collection.

(dotimes [_ (dec (count coll))] (print \.))

(println)))

(summarize ["Moe" "Larry" "Curly"]) ; -> Moe..

(summarize []) ; -> no outputThe condp macro is similar to a case statement in other languages. It takes a two parameter predicate (often = or instance?) and an expression to act as its second argument. After those it takes any number of value/result expression pairs that are evaluated in order. If the predicate evaluates to true when one of the values is used as its first argument then the corresponding result is returned. An optional final argument specifies the result to be returned if no given value causes the predicate to evaluate to true. If this is omitted and no given value causes the predicate to evaluate to true then an IllegalArgumentException is thrown.

The following example prompts the user to enter a number and prints the name of that number only for 1, 2 and 3. Otherwise, it prints "unexpected value". After that, it examines the type of the local binding "value". If it is a Number, it prints the number times two. If it is a String, it prints the length of the string times two.

(print "Enter a number: ") (flush) ; stays in a buffer otherwise

(let [reader (java.io.BufferedReader. *in*) ; stdin

line (.readLine reader)

value (try

(Integer/parseInt line)

(catch NumberFormatException e line))] ; use string value if not integer

(println

(condp = value

1 "one"

2 "two"

3 "three"

(str "unexpected value, \"" value \")))

(println

(condp instance? value

Number (* value 2)

String (* (count value) 2))))The cond macro takes any number of predicate/result expression pairs. It evaluates the predicates in order until one evaluates to true and then returns the corresponding result. If none evaluate to true then an IllegalArgumentException is thrown. Often the predicate in the last pair is simply true to handle all remaining cases.

The following example prompts the user to enter a water temperature. It then prints whether the water is freezing, boiling or neither.

(print "Enter water temperature in Celsius: ") (flush)

(let [reader (java.io.BufferedReader. *in*)

line (.readLine reader)

temperature (try

(Float/parseFloat line)

(catch NumberFormatException e line))] ; use string value if not float

(println

(cond

(instance? String temperature) "invalid temperature"

(<= temperature 0) "freezing"

(>= temperature 100) "boiling"

true "neither")))Iteration

There are many ways to "loop" or iterate through items in a sequence.

The dotimes macro executes the expressions in its body a given number of times, assigning values from zero to one less than that number to a specified local binding. If the binding isn't needed (card-number in the example below), an underscore can be used as its placeholder. For example:

(dotimes [card-number 3]

(println "deal card number" (inc card-number))) ; adds one to card-numberNote that the inc function is used so that the values 1, 2 and 3 are output instead of 0, 1 and 2. The code above produces the following output:

deal card number 1

deal card number 2

deal card number 3The while macro executes the expressions in its body while a test expression evaluates to true. The following example executes the while body while a given thread is still running:

(defn my-fn [ms]

(println "entered my-fn")

(Thread/sleep ms)

(println "leaving my-fn"))

(let [thread (Thread. #(my-fn 1))]

(.start thread)

(println "started thread")

(while (.isAlive thread)

(print ".")

(flush))

(println "thread stopped"))The output from the code above will be similar to the following:

started thread

.....entered my-fn.

.............leaving my-fn.

thread stoppedList Comprehension

The for and doseq macros perform list comprehension. They support iterating through multiple collections (rightmost collection fastest) and optional filtering using :when and :while expressions. The for macro takes a single expression body and returns a lazy sequence of the results. The doseq macro takes a body containing any number of expressions, executes them for their side effects, and returns nil.

The following examples both output names of some spreadsheet cells working down rows and then across columns. They skip the "B" column and only use rows that are less than 3. Note how the dorun function, described later in the "Sequences" section, is used to force evaluation of the lazy sequence returned by the for macro.

(def cols "ABCD")

(def rows (range 1 4)) ; purposely larger than needed to demonstrate :while

(println "for demo")

(dorun

(for [col cols :when (not= col \B)

row rows :while (< row 3)]

(println (str col row))))

(println "\ndoseq demo")

(doseq [col cols :when (not= col \B)

row rows :while (< row 3)]

(println (str col row)))The code above produces the following output:

for demo

A1

A2

C1

C2

D1

D2

doseq demo

A1

A2

C1

C2

D1

D2The loop special form, as its name suggests, supports looping. It and its companion special form recur are described in the next section.

Recursion

Recursion occurs when a function invokes itself either directly or indirectly through another function that it calls. Common ways in which recursion is terminated include checking for a collection of items to become empty or checking for a number to reach a specific value such as zero. The former case is often implemented by successively using the next function to process all but the first item. The latter case is often implemented by decrementing a number with the dec function.

Recursive calls can result in running out of memory if the call stack becomes too deep. Some programming languages address this by supporting "tail call optimization" (TCO). Java doesn't currently support TCO and neither does Clojure. One way to avoid this issue in Clojure is to use the loop and recur special forms. Another way is to use the trampoline function.

The loop/recur idiom turns what looks like a recursive call into a loop that doesn't consume stack space. The loop special form is like the let special form in that they both establish local bindings, but it also establishes a recursion point that is the target of calls to recur. The bindings specified by loop provide initial values for the local bindings. Calls to recur cause control to return to the loop and assign new values to its local bindings. The number of arguments passed to recur must match the number of bindings in the loop. Also, recur can only appear as the last call in the loop.

(defn factorial-1 [number]

"computes the factorial of a positive integer

in a way that doesn't consume stack space"

(loop [n number factorial 1]

(if (zero? n)

factorial

(recur (dec n) (* factorial n)))))

(println (time (factorial-1 5))) ; -> "Elapsed time: 0.071 msecs"\n120The defn macro, like the loop special form, establishes a recursion point. The recur special form can also be used as the last call in a function to return to the beginning of that function with new arguments.

Another way to implement the factorial function is to use the reduce function. This was described back in the "Collections" section. It supports a more functional, less imperative style. Unfortunately, in this case, it is less efficient. Note that the range function takes a lower bound that is inclusive and an upper bound that is exclusive.

(defn factorial-2 [number] (reduce * (range 2 (inc number))))

(println (time (factorial-2 5))) ; -> "Elapsed time: 0.335 msecs"\n120The same result can be obtained by replacing reduce with apply, but that takes even longer. This illustrates the importance of understanding the characteristics of functions when choosing between them.

The recur special form isn't suitable for mutual recursion where a function calls another function which calls back to the original function. The trampoline function, not covered here, does support mutual recursion.

Predicates

Clojure provides many functions that act as predicates, used to test a condition. They return a value that can be interpreted as true or false. The values false and nil are interpreted as false. The value true and every other value, including zero, are interpreted as true. Predicate functions usually have a name that ends in a question mark.

Reflection involves obtaining information about an object other than its value, such as its type. There are many predicate functions that perform reflection. Predicate functions that test the type of a single object include: class?, coll?, decimal?, delay?, float?, fn?, instance?, integer?, isa?, keyword?, list?, macro?, map?, number?, seq?, set?, string? and vector?.

Some non-predicate functions that perform reflection include ancestors, bases, class, ns-publics and parents.

Predicate functions that test relationships between values include: <, , =, not=, ==, >, >=,compare, distinct? and identical?.

Predicate functions that test logical relationships include: and, or, not, true?, false? and nil?

Predicate functions that test sequences, most of which were discussed earlier, include: empty?, not-empty, every?, not-every?, some and not-any?.

Predicate functions that test numbers include: even?, neg?, odd?, pos? and zero?.

Sequences

Sequences are logical views of collections. Many things can be treated as sequences. These include Java collections, Clojure-specific collections, strings, streams, directory structures and XML trees.

Many Clojure functions return a lazy sequence. This is a sequence whose items can be the result of function calls that aren't evaluated until they are needed. A benefit of creating a lazy sequence is that it isn't necessary to anticipate how many items in it will actually be used at the time the sequence is created. Examples of functions and macros that return lazy sequences include: cache-seq, contact, cycle/code>, distinct, drop, drop-last, drop-while, filter, for, interleave,interpose, iterate, lazy-cat, lazy-seq, line-seq, map, partition, range, re-seq, remove, repeat, replicate, take, take-nth, take-while and tree-seq.

Lazy sequences are a common source of confusion for new Clojure developers. For example, what does the following code output?

(map #(println %) [1 2 3])When run in a REPL, this outputs the values 1, 2 and 3 on separate lines interspersed with a sequence of three nils which are the return values from three calls to the println function. The REPL always fully evaluates the results of the expressions that are entered. However, when run as part of a script, nothing is output by this code. This is because the map function returns a lazy sequence containing the results of applying its first argument function to each of the items in its second argument collection. The documentation string for the map function clearly states that it returns a lazy sequence.

There are many ways to force the evaluation of items in a lazy sequence. Functions that extract a single item such as first, second, nth and last do this. The items in the sequence are evaluated in order, so items before the one requested are also evaluated. For example, requesting the last item causes every item to be evaluated.

If the head of a lazy sequence is held in a binding, once an item has been evaluated its value is cached so it isn't reevaluated if requested again.

The dorun and doall functions force the evaluation of items in a single lazy sequence. The doseq macro, discussed earlier in the "Iteration" section, forces the evaluation of items in one or more lazy sequences. The for macro, discussed in that same section, does not force evaluation and instead returns another lazy sequence.

Using doseq or dorun is appropriate when the goal is to simply cause the side effects of the evaluations to occur. The results of the evaluations are not retained, so less memory is consumed. They both return nil. Using doall is appropriate when the evaluation results need to be retained. It holds the head of the sequence which causes the results to be cached and it returns the evaluated sequence.

The table below illustrates the options for forcing the evaluation of items in a lazy sequence.

| Retain evaluation results | Discard evaluation results and only cause side effects | |

|---|---|---|

| Operate on a single sequence |

doall |

dorun |

|

Operate on any number of sequences |

N/A | doseq |

The doseq macro is typically preferred over the dorun function because the code is easier to read. It is also faster because a call to map inside dorun creates another sequence. For example, the following lines both produce the same output:

(dorun (map #(println %) [1 2 3]))

(doseq [i [1 2 3]] (println i))If a function creates a lazy sequence that will have side effects when its items are evaluated, in most cases it should force the evaluation of the sequence with doall and return its result. This makes the timing of the side effects more predictable. Otherwise callers could evaluate the lazy sequence any number of times resulting in the side effects being repeated.