The Importance of Contextual Design in Reducing Project Costs and Increasing Customer Satisfaction

By Angella Derington, OCI Software Engineer

March 2008

What is Contextual Design?

Contextual design (C.D.) is a scientific method for determining how software should be developed based on the users' actions and not their words. C.D. utilizes three distinct steps to help determine and prioritize software requirements.

- Contextual Inquiry. Gather data from observing multiple different users doing their work

- Work Modeling. Use standard modeling methods to model the individual user's work

- Consolidation. Consolidate all of the individual work models to create a complete view of users' work practices

After consolidation, the C.D. team can make recommendations on software requirements and prioritizations based purely on how users will actually use the software.

Unlike traditional methods of requirements gathering, C.D. has the ability to objectively determine and prioritize requirements, even with the influence of those "token" requirements being pushed by influential customer and/or project team members. And I would bet that most of us have been on projects where the sum of the most resource-consuming parts of the project were these "token" requirements.

Are you convinced yet?

Maybe you're thinking:

- "Why shouldn't we just trust the users to be able to put together a comprehensive list of requirements with accurate prioritization? After all, they're the ones that are going to use the software for their work."

- "Isn't C.D. just another way to charge customers more money?"

- "This sure sounds like another way to 'waste' time during the design phase of a project; let's just get to the good stuff: writing software!"

Let's do a little exercise to illustrate why customers might not be able to accurately describe their work, and therefore might have holes in the requirements or inefficient prioritization.

Contextual Design Exercise: Car Driving Software

Let's say that we are going to write software that does the work of driving a car, something along the lines of a precursor to the cars in "Demolition Man."

Your exercise is to think up the requirements for that software and its priorities. Do you have them ready?

So your top requirements might go something like this:

- Ability to turn on the car

- Ability to turn left and right

- Ability to accelerate and decelerate

You might even have thought about requirements like:

- Ability to turn on and off the wiper blades

- Ability to activate turn signals

- Ability to turn on and off the headlights

Now, just to make it realistic, let's throw in some "token" requirements from those influential team members.

- Ability to turn on air-conditioned seats

- Ability to adjust built-in air fresheners

Now we're ready to develop great software that every driver in the world will want in his or her next new car, right?

Our software developers have what they need to design software that provides the necessary functionality in a way that users will find easy to use and understand, right?

Developers should be able to design this software easily; after all, we all drive cars and know how they should work.

But ... our project manager has been under the gun because our team keeps having problems with scope creep, release slipping, and increased costs. And to top it off, when our software finally gets into the hands of our end-users, they are not happy with the software, and our customer service expenses keep going up.

Someone on our team has heard of this new design methodology, Contextual Design, that is supposed to help with this process. It is supposed to help our team figure out what features are really important to our users and how our users will actually use those features, which should hopefully reduce project costs and customer service calls. Our project manager decides to take a risk on this new methodology to see if it will help. After all, her understanding is that C.D. should take only 4-5 weeks, and our project is being estimated at $5 million dollars and a 2-year timeline.

Step O: Get prepared for Contextual Design

The first step in C.D. is Contextual Inquiry (C.I.), a fancy term for observing and interviewing people while they do the work with which the software is going to help.

Before we can start our C.I. step, we need to line up our potential interviewees. So, we need to answer a few key questions:

- Who are our target users?

- How many people do we need to interview to get a good cross-section of our target users?

- How many team members are good candidates for C.I. work?

- How many of those team members can we devote to the C.D. process?

- What type of work do we want to observe?

Then we'll set up the interviews and get started!

1. Who are our target users?

In order for C.D. to be effective, our interviewees should be good representatives of our target users; otherwise we will not get valuable data from our analysis.

For this study, let's assume that our marketing department thinks that our driving software will be most appealing to drivers on road trips and long commutes, both with and without children in the vehicle. So, we obviously need some parents who travel with their children and some commuters.

Is that all?

It might be good to also ask marketing who else they think might be interested in this software in the future, which turns out to be technophiles and the elderly.

So, now we know the sub-groups of people that we want to interview.

2. How many people do we need to interview?

We need to figure out how many interviewees we should find for each subgroup in order to achieve a good cross-section of our target users.

In practice, interviewing at least four different people from each of our primary groups (in this case, families and commuters) will generally provide adequate data coverage. Interviewing one to two additional interviewees from each of our "future user" groups (technophiles and the elderly) will provide adequate outlier coverage.

However, as the analysis progresses, it may become necessary to add more interviewees to answer any significant questions that may arise.

3. How many team members are good candidates for C.I. work?

The next step can often be the most daunting for a development team, especially one that does not have prior experience with C.D. analysis. The team leaders need to ask, "who on our team would even be good at doing this, let alone want to give up "real" development for 4-5 weeks?"

For C.I., it is preferable to have one facilitator and one observer for every interview.

- Facilitator. The facilitator's primary job is to help the user understand the C.I. team's expectations and to ask clarifying questions during the interview.

- Observer. The observer's primary job is to take thorough notes of the user's actions and commentary. Since the facilitator will be busy conducting the interview, and thus unable to take extensive notes, this job is very important.

- It is important to note, that it is preferred that the observer not speak to the user during the interview. This is to reduce confusion with the user and to better facilitate the observer's ability to take complete notes.

C.I. takes patience and strong observation skills, and not all developers are a good fit for C.I. work, especially those that like to work in a silo and those that strongly prefer coding over designing. Most developers, however, become strong believers in C.D. after participating in the process.

The most important trait in selecting team members for C.I. work is their attitude toward designing software. A C.I. team member needs to believe that software should be designed to best fit the users' needs, over what is "cool" technologically, what has been done before, or what is easiest to develop.

C.I. is all about users and user needs, so team members need to be able to see the world from that perspective.

4. How many of those team members can we devote to the C.D. phase?

Many development teams may have only a few people who are good candidates for C.I. work, and some of those people may be your most important developers. This is when the project or development manager needs to decide how important the C.D. analysis is to the project in relation to the tasks that these developers are working on now.

Contextual Design Timeline

Each phase of C.D. takes a certain amount of time and manpower, so in order to figure out how many people to devote, we need to figure out how much time we need to complete our analysis.

- Contextual Inquiry. Approximately 2 hours and 2 people per interview

- Work Modeling. Approximately 2 hours per interview; should be conducted in the same day as the C.I., if possible

- Consolidation. 1-2 weeks, depending on variations in data collected during the C.I. and Modeling stages

- It is beneficial to have as many team members as possible participate in this step. This step can help developers better understand how users will use the software, which generally leads to better design decisions during the design and implementation stages of the project.

The C.D. has decided that the following interviews are necessary:

- 4 families

- 4 commuters

- 2 technophiles

- 1 elderly person

- 11 interviews total

If the team performs only one interview per day, we could complete the C.I. and modeling phases in about three weeks (given days off, travel time, etc.). That seems doable for our team: three weeks and only two team members off active development. The main concern, however, is that we now have only two people doing the modeling. Is that going to give us good results?

It is preferred to conduct C.I. with two teams working in tandem, with the teams conducting separate interviews in the morning and then performing modeling work together in the afternoon. This allows for deeper discussions around what the interviewee really meant and potential holes in understanding the users' actions.

For this exercise, however, we will assume our manager is only approving one two-person team, since we are new at C.D., and she is still not convinced that this is the best use of the team's resources.

5. What type of work do we want to observe?

Before the team goes into an interview, we need to figure out what kind of work we want to observe.

In our case, we want to observe our users driving a car. It would also be helpful to see (or at least hear about) the actions leading up to and after driving a car. These pre and post actions can give us important tidbits of information on how we can add value to our application.

Time to Set up interviews and get started!

Now that we have a team, a timeline, and the work we want to observe, we need to set up interviews with users in our desired groups. Let's assume that we have people in our organization who can get us names and numbers of interested users that fit into our subgroups.

When setting up interview times, one of the most important pieces of information we need to transfer to our users is that we want to watch them actually performing the work we want to observe. This can be a difficult concept for users to comprehend, since they probably have never had an experience where an interview is based on actions and not on words.

For our example, we will want to encourage our users to have a natural reason to drive their cars during our interview with them. So, we want to observe a parent driving a car with children and a commuter going to work in the morning.

Now we're ready to get started!!

Step 1: Contextual Inquiry - Gather the data

There are three primary parts of Contextual Inquiry:

- Warm up. Reiterate with the user what to expect during the interview

- Observe the work. Observe and clarify the user's actions

- Wrap up. Clarify the high-level actions observed and ask follow-up questions

1. WARM UP. REITERATE WITH THE USER WHAT TO EXPECT DURING THE INTERVIEW

After our initial "meets-and-greets" with the user, we will want to reiterate why we are here and what work we would like to observe him or her performing.

The following points are the most important to present to the user:

- You are here to help in designing new software for driving a car; we want to use the actions of actual car drivers to help us design software that will better meet their needs.

- It is important for you to perform actions just as you would if we were not here.

- We're not here to judge you and will not let any "less desirable" actions be linked back to you. All of your actions, both the good and the bad, are important for us to see, so we can get a full picture of how our users perform their work.

- For our example, we could say that "less desirable" actions that we would still want to see could include speeding, failure to use a seat belt, talking on a cell phone while driving, etc.

- We would like you to talk through your actions.

- For example, when you turn on the turn signal, we would like you to say what you are doing and why; "I'm turning on the turn signal because I need to change lanes to get to my exit."

- The facilitator will ask clarifying questions about your actions while they are being performed.

- For example, after you have engaged the turn signal, the facilitator might ask "I see that you turned on your turn signal to change lanes; do you always use a turn signal or are there times when you do not use a turn signal?"

- There will be an opportunity at the end of the interview for you, the facilitator, and the observer to ask follow-up questions, but during the interview, we would like to stay focused on your actions.

After the facilitator has presented our key expectations to the user, the facilitator should make sure that the user understands these expectations, and then we are ready to observe some driving!

2. Observe the work. Observe and clarify the user's actions

Now we are in the meat of C.I., actually observing the user perform the work.

Facilitator Responsibilities

The flow of this part of C.I. is mostly determined by the user, but it is the facilitator's responsibility to keep the user on track.

Some things the facilitator needs to be cognizant of are:

- Making sure the user stays in the present

- Some users will start going down a "reminiscing" path, talking about how they used to do their task or how someone else does their task.

- For our example, the user could start talking about how he always uses his turn signal, but that his wife rarely uses hers. This information is important, so the observer should take notes on what the user says, but the facilitator should steer the user back into the present by asking questions about what the user is presently doing, "I see that you just looked over your shoulder, why did you do that?"

- Encouraging the user not to look to the facilitator or observer for guidance.

- Some users will ask the facilitator for guidance on particular task.

- For example, the user could ask "I can never remember how to turn on my fog lights when we have these foggy mornings. Do you know how to do that?" In these cases, it's important for the facilitator to reiterate that we want to see how the user performs these tasks, and that our data will not be accurate if the facilitator takes a role in performing the task.

- Keeping the user talking through his or her actions.

- If the user stops talking through his or her actions and just does them (which will happen frequently, because the user is not accustomed to talking out loud while performing routine tasks), the facilitator should ask clarifying questions about what just happened and reiterate how helpful it is to us if the user talks through his or her actions and explains why he or she is doing that.

The most important thing for facilitators to keep in mind is that it is better to feel like they are asking too many questions than to get to the modeling step and not understand why the user did something.

In C.D., the whys behind actions can be the most important information in determining requirements and priorities.

Observer's Responsibilities

It may seem that the observer does not have a very important role during C.I., but in practice, the observer's role can be the most important.

During the interview, it is the observer's responsibility to watch and listen closely to the user and the facilitator and record everything the observer sees and hears. The smallest of details can be critical to creating a complete picture of the user's actions and intentions during the modeling and consolidation steps.

Often, the facilitator will not pick up on every hole in his or her understanding of the user's actions, and the little details that the observer records can give clues to those answers.

For example, the user may flash his or her lights, but the facilitator may not know why. The observer could have noticed that a car on the other side of the road did not have its lights on, and our user was trying to inform the other driver of the problem.

3. Wrap up. Clarify the high-level actions observed and ask follow-up questions

Once the user feels that he or she has completed the tasks we are there to observe, we move into the wrap up.

During wrap up, the facilitator has a few key tasks:

- Most important! Thank the user for his or her time and reiterate how helpful the information that we gathered will be to our project.

- Repeat to the user the high-level steps that were observed while user worked through the tasks. This step can also be performed during the interview when the user changes between high-level tasks.

- If the user referenced any unique artifacts (documents, notes, etc.), ask if the team can get a copy of them for reference.

- Ask the observer if he or she has any questions about what he or she observed the user doing.

- Don't forget this task, because the observer may have some important clarifying questions for the user.

After wrapping up what was observed during the interview, the facilitator should give users an opportunity to ask questions of the facilitator and observer, as well as to add any additional information that they think is important for the team to know.

Some useful information that can be gathered at this point is:

- Actions that the user needs to perform occasionally, but were not observed today

- Individual tasks during their work that they feel are a pain and could be designed better

- Functionality that they would like to be provided in the software

Before leaving users, thank them again for allowing you to disrupt their day and reiterate how important the information that you've gathered is.

Step 2: Work Modeling - Model the data gathered

Work modeling allows us to organize the raw information that we gathered during C.I. in a methodical, scientific way, and is crucial to the outcome of C.D.

The work modeling process is as follows:

- Both members of the interview team simultaneously read through their notes for the modeling team.

- After each individual observation, the modeling team decides in which model the observation belongs.

- During this exercise, it is the other team members' responsibility to make sure they fully understand the sequence of events.

- By creating the work models on the same day as the interview, the interview team may be able to remember more details about the interview because of the other team members' probing.

C.D. utilizes several model types:

- Flow model. Tracks the flow of information between different people

- Sequence model. Tracks the user's intentions and actions consecutively

- Physical model. Graphical model of the user's work environment

- Culture model. Records any important influences, rules, etc. placed on the user because of the culture of the work environment

- Observations. Any other important information presented by the user that does not fit into one of the other models

Contextual Design Recording Standards

C.D. uses three colors to highlight different types of data. The purpose of using these different colors is to help the C.D. team better analyze the models during consolidation.

- Red. User breakdowns

- Events or actions that caused the user to be less than successful or caused inefficiencies in the user's work

- Green. Non-observed data

- Events or actions only described by the user, but that were not actually observed during the interview

- This data should not be given as much weight during consolidation, because users' memories of events are not as complete as observations.

- Black/Blue. All other data

- All events or actions that were observed during the interview

1. Flow Model

The purpose of the flow model is to record the flow of information and artifacts (paperwork, containers, etc.) between people during the execution of the user's work.

C.I. data that should go into a flow model for our driving software could include:

- Commuter flashes lights at an oncoming car

- Mother hands juice box to child behind her

- Child passes forward a drawing that he or she just made to the parent

- Outside driver honks at our elderly driver

Figure 1. Example flow model (reference: groups.sims.berkeley.edu/waypoint)

2. Sequence Model

The purpose of the sequence model is to record the user's intentions and the actions taken to address that intent in a consecutive manner.

In practice, this model is the most important; it clearly displays the user's high-level goals and the steps necessary in order to address those goals.

Sequence model is also the most complex of the models, so for this article, I will be giving only a high-level overview of how to create a sequence model. If you are interested in learning how to create a sequence model in practice, please check out the additional resources listed at the end of this article.

Creating a Sequence Model

- Write down sequence actions in the order they occurred

- Sometimes actions will be recorded out of order during C.I. This can occur either because the user is describing events that took place in the past or because the note taker wrote down actions out of order for some reason.

- The importance of the sequence model is to understand the order of the steps the user needs to take to address the task

- Determine what the user's intent was for performing the actions

- This is the most important aspect of the sequence model. In order to accurately determine requirements and priorities, it is imperative that the C.D. team understand why the user did what what was done.

- Every series of actions should have a corresponding intent by the completion of the sequence model.

- Intentions should be nested as the user's intentions become more detailed.

- The intentions will become the outline for the sequence model.

Example Sequence Model

- Intent: User needs to go to work

- Intent: User needs to get settled into the car

- User sets coffee cup in the cup holder

- User plugs his cell phone into the car adapter

- Intent: User needs to re-adjust car settings, because wife was last driver

- User adjusts seat

- User adjusts side and rear view mirrors

- User adjusts steering wheel

- User buckles seat belt

- Intent: User needs to back-out of the garage

- ...

- ...

- ...

- Intent: User needs to get settled into the car

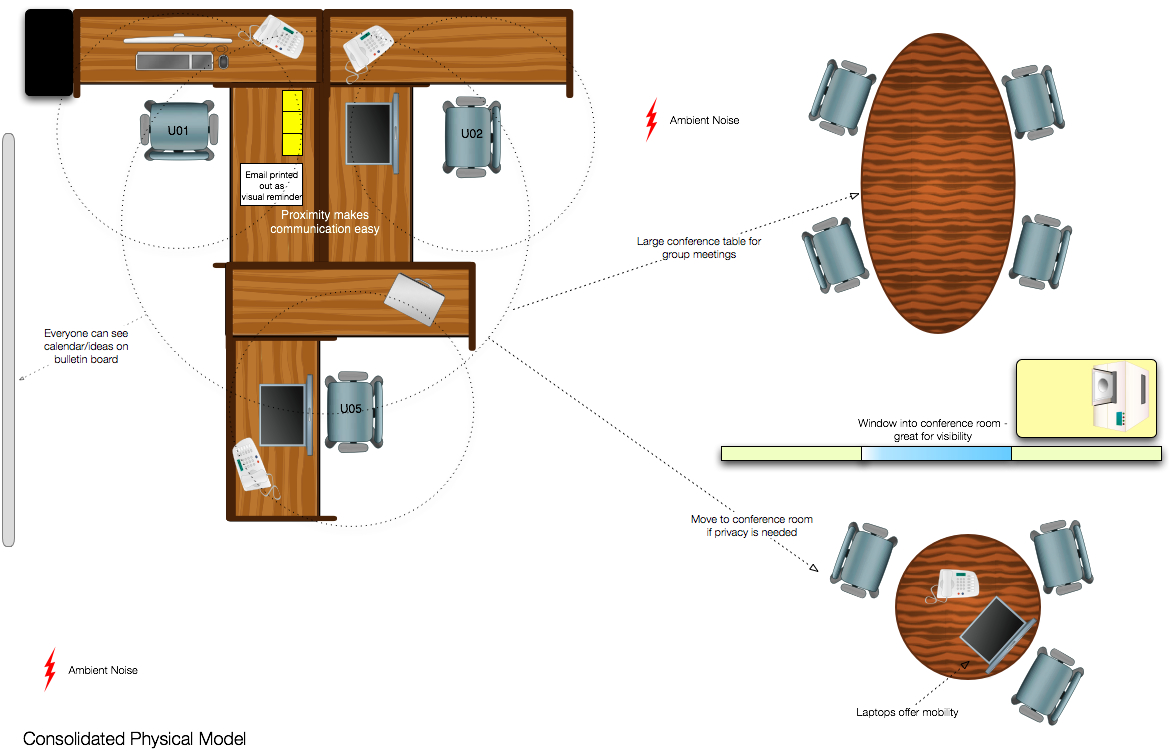

3. Physical Model

The purpose of the physical model is to record any important information regarding the user's physical work environment.

This model is generally recorded as a rough drawing of the interesting aspects of the user's environment. In practice, a physical model is only done if interesting data was observed during the interview that is attributed to the user's physical environment. The physical model can identify inefficiencies or breakdowns in the user's work. The physical model can also identify potential limitations on the software.

C.I. data that could indicate a need for a physical model includes:

- The user had to search around for the play button for the DVD player

- The user had to reach into the glove compartment to find a map of the area

Figure 2. Example physical model (reference: supernovel.wordpress.com)

4. Culture Model

The purpose of the culture model is to record any influences on the user's actions that are attributed to politics, work culture, rules of conduct, etc. In practice, a culture model is rarely created, because there are rarely enough different pieces of information to make it useful; interesting culture observations are instead recorded in the observation.

An example of C.I. data that could go into a culture model might be that "the husband speeds, but only when his wife isn't looking."

5. Observations

Observations are all of the other data that was recorded during C.I. that could not be attributed to one of the above models.

Observations are generally recorded as a bulleted list. Observations can also include any design ideas that the team thought of and any questions that arose during the modeling session.

Step 3: Consolidation - Make a complete view of the data

Once all of the interviews have been conducted and modeled, it is time to create the consolidated models from the individual work models.

At this point, it is beneficial to the project to have other members of the development team participate. In practice, it has been found that project team members retain more of the knowledge gained from C.D. by being involved in the analysis phase, even if they do not spend 100% of their time with the C.D. team. This knowledge in turn benefits the project by having more people on the team understanding the use cases and customer needs.

We will be creating consolidated models of each of the model types we created for the individual interviews, plus two additional models:

- Affinity diagram. Hierarchical model of relationships between the data gathered in the observations

- Artifact model(s). Model(s) that demonstrate the important aspects of related artifacts

In practice, it is most useful to consolidate the models with the least data first. Often, those models include the physical, culture, artifact, and flow models. Sometimes individual models are not easily consolidated, such as the physical model, and in those cases, it is acceptable to keep the individual models separate for the analysis phase.

The most important thing to remember during consolidation is that the goal is to organize the data in such a way that it can assist the team in clarifying the requirements and priorities needed for our software project.

Consolidation: Sequence Model

Once again, I'll provide a brief overview of creating a consolidated sequence model; if you would like to learn how to create a sequence model in practice, please reference the resources at the end of this article.

To consolidate the sequence model, we will start by:

- Identifying similar intents in each of the individual sequence models

- Identifying the sequences of events that match up to similar intentions

- Add intents with decreasing similarity until all of the items in the individual sequence models are in the consolidated sequence model

The consolidated sequence model will start to look and feel a lot like pseudo-code. The consolidated model will most likely have if/else statements and variations to the intentions.

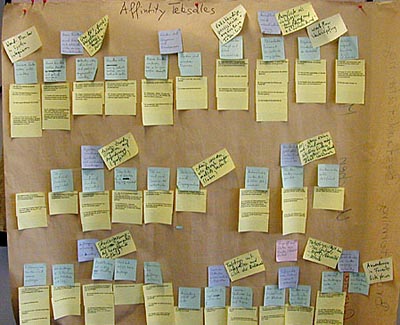

Consolidation: Affinity Diagram

The creation of the affinity diagram is an ideal activity to involve the larger project team. The purpose of the affinity diagram is to organize all of the observations by their relationships to each other.

Creating an affinity diagram is an organic process that involves immersing the team in the observations left out of the other models.

- Place each individual observation on its own small piece of paper

- Team members start organizing the observations by placing each one near other observations that seem related (no right or wrong answers)

- Team members can move observations around even after a relationship is first identified

- Relationship groups will start to form; each group should have six or fewer items in each group

- After all of the observations have been placed in relationship groups, each team member attempts to create a description of the groups

- The team decides on one description for each group; the team can decide to use one of the members' descriptions or create a new description

- The relationship groups are now placed near other groups that seem related

- Second-level relationship groups will start to form. Each second-level group should contain six or fewer first-level groups

- Descriptions are written for each second-level group, just like for the first-level groups

- Steps 7-9 are repeated until we have five or fewer high-level relationship groupings

At any time during this process, observations and relationship groups can be moved around to make better relationship groups.

Figure 3. Example affinity diagram (reference: www.sapdesignguild.org)

The affinity diagram will be a strong indication of requirements and priorities needed by the application. It will also quickly show additional value-added features that can be added to application in the future.

Requirements and Priorities Analysis

At this point the C.D. team has all of the C.I. data modeled in an objective way and can begin identifying the requirements revealed by the models and their appropriate priorities.

For ease of understanding, let's prioritize our requirements into three buckets:

- Must Haves. Requirements that must be in the application for it to be beneficial to users

- Important to Haves. Requirements that are not absolutely necessary for the application to be beneficial to users, but would add useful functionality

- Nice to Haves. Requirements that do not add significant functionality, but may be important to some users. These are "bells and whistles" kinds of requirements.

Now that we have our three buckets filled with the requirements ascertained from our C.D. analysis, our marketing department or customer team can decide what requirements should be included in the first release of our application. And the coding can begin!!

Other Benefits of Contextual Design

Beyond knowing what requirements are really important for users, there are many more benefits to conducting a C.D. analysis. These include:

- Reduced project costs. C.D. will reduce project costs through reduced scope creep and rework costs.

- Requirements are captured from the users' actions, so rework tasks from not providing the right functionality become negligible.

- Requirements are prioritized by the objective modeling of several representative users, so scope creep can be managed by referring to the C.D. analysis data.

- Increased adoption rates. Users are much more likely to embrace new (or improved) applications that are designed around their needs.

- 80/20 rule. In most software, 20% of functionality is used 80% of the time.

- Contextual design can identify the most used functionality; developers can design and implement these features so that they are the most stable and easiest to use.

- Project managers and quality assurance personnel can focus on these functionality features to ensure stability and completeness of requirements.

- Concentrating on the 80/20 functionality will further increase adoption rates, because users' expectations are generally exceeded.

- Identification of value-added features. C.D. can identify functionality that can be leveraged to offer additional value-added features to the user.

- This can extend the life of the application through upgrades, plugins, etc.

- This can identify companion products and other revenue lines.

- Increased understanding of user needs. C.D. provides the ability to expose all of the project team members to the user needs for an application.

- This can improve UI and workflow decisions.

- This can help team members re-align their thinking to keep user needs as their top priority when making design decisions.

References

- [1] Contextual Design: A Customer-Centered Approach to Systems Designs By: Hugh Beyer and Karen Holtzblatt

- [2] Rapid Contextual Design: A How-to Guide to Key Techniques for User-Centered Design By: Hugh Beyer and Karen Holtzblatt

Software Engineering Tech Trends (SETT) is a regular publication featuring emerging trends in software engineering.